Puja Bhattacharjee

Date | April 28, 2016

Photos courtesy: CIL

Photos courtesy: CIL

A few kilometres from the Dhanbad railway station lies Jharia Coal Field (JCF), one of the biggest coalfields in India. It is also the biggest mine under Bharat Coking Coal Limited (BCCL), a subsidiary of Coal India Limited (CIL), in Jharkhand. As the car makes its way through Dhanbad town, the driver points to his right and says, “This is Wasseypur” – the town made famous by a Bollywood movie. As we near the coal mine, the road curves upward in a spiral. The terrain changes and the car seems to be driving up a hilly road. Puzzled, I wonder if Dhanbad is part of the Chhotanagpur plateau. As the car keeps moving up the twisted road, I realise that we are nearing an open cast mine.

Unlike underground mining, in open cast mines like JCF, the earth is stripped of soil, sand and rocks through digging and blasting to reach the coal seams. As mining progresses, the mass of soil and rocks, called ‘overburden’, piles up in mounds which will remain there till the mining is over. The gaping hole on the ground will then be filled with the overburden. The road cuts through the undulating overburden. Inside the active mining area, gigantic shovels with thick iron claws tear away the coal which is lodged in the earth and load it on dumpers.

On another side, tall drills work their way into the ground digging up white dust. At two o’clock in the afternoon, the mine will be vacated, the drilled ground will be filled with explosives and at the touch of a finger the earth will come loose from the ground. Expansion and mining take place side-by-side in open cast mines. All machinery in open cast mines are operated by electricity but the poles supporting the electric wires change location with the shifting mining activities.

A lone truck sprays water on the mine ground to prevent dust pollution. It is not enough: I cannot see the mine clearly even from a higher vantage point. It is enveloped in smog. It is strictly forbidden to enter the mine without safety gear. Still, people from neighbouring villages often sneak in and sort through discarded rocks in the hope of finding coal. Sometimes they succeed.

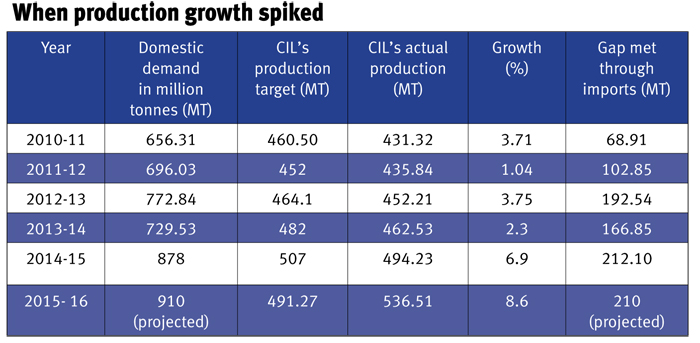

Today 93 percent of the total production of coal by CIL – India’s largest coal producer – is through open cast mines. Though India has vast quantities of natural resources, it was forced to import 212 million tonnes (MT) of coal in 2014-15, as the production and supply chain could not keep up with the rising domestic demand. In the annual plan for 2015-16, domestic coal demand had been assessed to be 910 MT. In 2014-15, CIL produced 494 MT, an increase of 32 MT over the previous year. This figure was more than the cumulative growth of previous four years (31 MT). In 2015-16, CIL has reported 8.6 percent growth in production.

For a once-beleaguered public sector undertaking (PSU), this is quite an achievement. Last year in November, Piyush Goyal, minister of state with independent charge for power and coal, had said that CIL was expected to produce 500 MT coal in 2015-16 which would go up to 1 billion tonnes in 2019. He had further noted that by 2017 CIL will be able to fully meet the domestic coal demand.

Bureaucratic maze

Seated in his spacious office in Shastri Bhavan in Delhi, Anil Swarup, secretary, ministry of coal, says that this growth was thanks to three major factors: ease in land acquisition, swift environment and forest clearance and speedy evacuation of coal. Swarup was earlier in the project monitoring group of the cabinet secretariat. He is known for his unconventional and dynamic approach to problem solving. The image of the coal ministry was heavily dented when in 2014 the supreme court cancelled ‘arbitrary and illegal’ allocation of 214 coal blocks to private and public sector firms. The maverick Swarup was specially brought into the ministry to restore its credibility.

“We have set up a coal projects monitoring portal, ‘e-CPMP’, on which we upload all information on coal projects. We hold a meeting on a predetermined day and time in which we discuss all the issues threadbare with the concerned ministries,” he says, stressing each word to drive home the point. Even if he is burdened with expectations and enormity of the task, it does not show on his face. He seems in control.

Obtaining environmental clearance is one of the biggest hurdles to coal mining. In recent times, the coal ministry and CIL have been able to convince the ministry of environment, forest and climate change (MoEFCC) that they are “equally concerned about the environment” and are taking steps to conserve the environment.

“For every hectare of land we mine, 2.4 hectares of land are being forested. At the time of mining, the forest will seem ripped. As we are mining, we are creating another forest elsewhere and we also afforest the land once the mining is over,” says Swarup. He shows momentary disappointment as he laments that people in cities who talk of ill effects of mining do not get to know these facts.

The coal ministry ferried teams from the environment ministry to the mining sites to show them the environmental reclamation work CIL and its subsidiaries were taking up. “The idea was to establish a communication channel with all the stakeholders and convey to them that we are concerned about their concerns and we want them to be concerned for us as well,” Swarup says, swaying in his chair. To substantiate the claim, Swarup says that the afforestation work done by the CIL subsidiaries is closely monitored via satellite mapping by them in collaboration with the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) and the National Remote Sensing Organisation (NRSO). Last year CIL had acquired more than 2,500 hectares of land under the Coal Bearing Areas (Acquisition and Development) Act of 1957. In the next five years, to achieve the target of 1 billion tonne production, CIL will open one new mine every month, apart from expanding the existing ones.

To keep up with the production target, more than 40 environment and forest clearances have been procured in the last one year, Swarup declares triumphantly.

Land acquisition and rehabilitation of those who give up their land is an important aspect of open cast mining. CIL has eight subsidiaries which mine coal in different parts of India. Mining gets delayed if the subsidiaries are not empowered to take decisions and all permissions have to be routed through the Kolkata headquarters. Sutirtha Bhattacharya, chairman and managing director (CMD) of CIL, works from a longish office on the fifth floor of the company headquarters. He approaches the conversation cautiously, measuring each word. He says that subsidiaries have now been empowered to take decisions related to removing overburden. “Decision-making has to be facilitated at every level. At the same time, if there are issues, they have to be dealt with politely but firmly. In certain sensitive cases, situations have to be monitored and we have to respond in a well-thought manner.”

To understand how CIL managed to increase production, he says, we have to take note of two major factors relating to production: availability of land and harnessing technology to speed up mining on the ground. Delay in land acquisition is the biggest hurdle to mining. Interpretations of land related laws and rules can be tricky and CIL officials may not be always familiar with the intricacies of the problems on ground. So CIL started identifying veterans in the field with experience in areas such as railways and land acquisition. Retired personnel from state and central governments were brought into the team. “Small yet critical associations with the state and railways got us regulatory access. The aim of bringing people over was to optimise resources by taking optimal advice in a fair and transparent manner,” says Bhattacharya.

For example, Tapan Kumar Shome, who has joined CIL as adviser (land), is a retired IAS officer, and has served in West Bengal’s directorate (land records and survey) and also as the state’s secretary (land and land reforms). In acquiring land, companies routinely face problems due to unclear land titles or encroachment as well as from local political lobbies. This is where Shome’s experience and expertise come handy. CIL sorts out all policy issues with the state governments. Often there may be policy differences related to settlement of affected people. “In most cases we accept the terms of the state government,” Shome says.

“My experience helps clarify to the officials how they should approach the problem and who they should speak to. Before going for a meeting with state officials, I brief them what documents they must carry with them. Documentation is an important aspect of land. It decides whether the process will be expedited or impeded,” he says.

CIL is working on a web-based land information system (LIS) to monitor land acquisition, rehabilitation and resettlement process. “We are trying to create an online land bank system. When everything is online, it becomes easier to monitor,” says Shome. The LIS will also contain an inventory of mined and yet-to-be mined land.

Ground realities

Innovative measures that helped increase production

- CIL produced 536 MT coal in 2015-16 which is expected to go up to 1 billion tonnes in 2019

- Maximum coal produced by open cast mines

- The coal secretary and the CIL chairman-cum-managing director routinely engage with all stakeholders directly or via video-conferencing for speedy resolution of issues

- More than 40 environment and forest clearance have been procured in the last one year

- Afforestation work done by the CIL subsidiaries is closely monitored via satellite mapping by them in collaboration with the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) and the National Remote Sensing Organisation (NRSO)

- Rainwater is harvested to recharge the ground water lost during mining

- Since its inception CIL has planted 8,26,76,991 trees in a total area of 39,944.63 hectares

- Retired personnel from state and central land and railway departments have been brought into CIL to smoothen out issues related to land acquisition and transportation of coal

- Railways have introduced larger wagons to evacuate more coal and capacity of rakes increased

- To monitor pilferage of coal, coal carrying routes have been virtually geo-fenced and movement of trucks is monitored using GPS and RFID tags

- The marketing department of CIL strengthened to understand consumer needs

- CIL is working on a web-based land information system (LIS) to monitor land acquisition, rehabilitation and resettlement process

- Technology heavily used for mining and dispatch of coal. Excavation materials like explosives sourced through e-procurement to ensure transparency

On the ground, better dumpers and excavators have been employed to expedite mining. An imported software package called operator independent truck dispatch system (OITDS) has been deployed on experimental basis in large open cast mines like Mahanadi, northern and south-eastern coalfields. It has taken over the job of manually operating shovels and dumpers. It tracks the functioning of the shovel and dumpers. If it senses that a dumper has been idle for more than five minutes, it routes it to the loading point, thereby enabling speedy dispatch. This technology will be introduced in more mines depending on its success.

It is through such technical improvements and of course through better training that Coal India has been able to increase production even though its total employee strength today is less than last year’s, points out Swarup. “We are also experimenting with ‘long wall technology’ in mining. If it works, it can be replicated,” he adds.

Before coal reaches the mass dispatch area, it has to be transported from the mine. A fifth of the coal produced is stolen by mafia accruing losses to the tune of $1 billion annually to CIL. To minimise theft, CIL has brought in technological advancements. The whole route from the mine to the stockyard and coal handling plant has been digitally marked out, and truck movements (for example, crossing a fence) can be tracked and detected on the computer screen. “We are monitoring the movement of trucks. It has not totally eliminated but has brought down pilferage substantially,” says Swarup. The technology was first used in March 2013 in Mahanadi Coalfields Ltd (MCL). Once the truck is filled with coal, it is placed on a weighing platform secured by boom barriers; the weight is recorded through electronic weigh bridge. At the destination, the weight of the truck is measured again. Similarly, once the coal is loaded on railway wagons, the weight of wagons is measured using in-motion way bridge. A security team at the command and control centre monitors the movements of the trucks through GPS devices installed in them. Additionally, radio frequency identification (RFID) tags are also issued to distinguish between the trucks. In the central control room the security team monitors the movement of the vehicles. If a truck is lying stationary or ventures out of the virtual route mapped out, an alert is issued. The ground patrol team rushes to intercept the vehicle.

Evacuation assumes priority once coal is safely transported to the dispatch area. “Acquiring resources is not good enough. We have to have quicker access to those resources. Even if production is high but the coal cannot be evacuated, then it becomes a limiting condition,” says Bhattacharya.

Railway to the rescue

Railways carry 55 percent of the evacuated coal as other modes like roads transport and conveyor belts have limited volume capacity. In the past seven years, the average railway dispatch growth was 4.5 percent per year. It more than doubled last year. Railway dispatch growth during financial year 2015-16 was 9.3 percent. The current target is to transport 550 MT of coal via railways. To deal with the rising volume of coal, railways have introduced a larger wagon which accommodates 10 tonnes more of coal. With the carriage capacity taken care of, the ongoing exercise is to anticipate the likely growth of traffic in the railway network.

“My knowledge of coalfields, railway and power sectors, and rapport with power, coal and railway officials help in smooth transportation of coal from the collieries,” says AK Maitra who has over 36 years’ experience in the railways. He looks more like an erudite academician than a public servant. He has served as chief of freight transportation with the south-eastern railways, divisional railway manager (DRM) at Howrah, additional DRM at Sealdah, chief operations manager of eastern railways, additional member (traffic) and director (planning) on the railway board. He joined CIL as adviser (railways) in 2015. His brief is “to squeeze out more output from existing assets through better co-ordination with the railways”.

In the field of logistics, the USP of a veteran professional like Maitra is to be able to see bottlenecks and provide solutions. His typical day starts with reports of problems encountered during the previous day’s loading. He then speaks to officials of the CIL subsidiaries, managing directors or with erstwhile colleagues of railways. “Every problem has various views. I take their view of the problem,” he says. Due to his seniority and long association with the Indian railways, he can ask railway officials to tweak a stream slightly to aid in speedier evacuation of coal. During financial year 2013-14, average loading was 194 trains per day. In the next financial year, it went up to 213 trains per day. Maitra describes his job as “housekeeping at a gigantic scale”. There are seasonal fluctuations in the loading of coal. Steps have to be taken in advance to prepare for monsoons, when mines get flooded. It is Maitra’s task to continually engage with the subsidiaries from issues ranging from drainage to quality of roads for the smooth transportation of coal to mass dispatch areas.

In 2015-16, on average, 213 rakes were available per day and in October 2015, it reached 220 per day. It is not merely production that has grown; evacuation has also hastened. The actual growth of coal production during the last fiscal was 8.9 percent and evacuation was up by 10.8 percent. “We could convey to the railways that it was also in their interest to increase the capacity of rakes. The railways earn revenue from the rakes. Some 50 percent of the freight of railways is given by coal. If their conveyance of coal goes up then railways become the beneficiary,” says Swarup. “This appears very common-sensical but you need to keep hammering these points, then you get results,” he adds.

“How come the evacuation is more than the production?” he pre-empts the question and then proceeds to answer it. “At pitheads, coal was available which could not be transported at that time due to shortage of rakes. Now with the availability of rakes, the stock has been liquidated substantially.” There has been a twofold impact of the increase in production. The coal availability at power plants was for eight days in December 2014; it was more than 20 days in March 2016. Also, imports have come down by more than 10 percent in the last one year.

Future planning for movement of coal via the railways is important at this stage. With growth in production, the pressure to dispatch becomes high. The NDA government has taken up the expansion of the heavily saturated railway network to meet the coal evacuation target. In 2014-15, on average 58.5 trains were loaded per day. In 2015-16, the number rose to 63.7 trains per day. “Growth from the same infrastructure led to transportation of 20,000 tonnes more of coal,” says Maitra. His field-level expertise and ability to talk to railway officials about specific details makes a difference. He, however, insists he has done nothing exceptional. “I oiled the wheels. I did not bring a magic lamp. The basic trigger has been the increase in production which led to increased dispatch,” he adds.

The demand for coal has a direct bearing on production. Bhattacharya says CIL representatives routinely conduct meetings with the consumers to understand their need. The PSU has strengthened its marketing department. After 2009, the demand for coal in thermal power plants has increased manifold. About 75 percent of the total coal produced by CIL is utilised by power plants across the country. The rising demand led to increased production which culminated in record production. However, with economic slowdown in recent times, the demand for power has slumped. Power plants usually stock up 15-16 MT of coal. But now the stock has risen to 34 MT because it remains unused. “Some power plants are taking coal less than their trigger level,” admits LK Mishra, CIL’s general manager (sales and marketing). CIL also supplies coal to power plants with no linkages through e-auctions. The demand from such plants has been falling.

To keep up the pace of production, Bhattacharya routinely holds video conferences with district collectors, chief secretaries of states and the coal secretary for quick resolution of issues. “Each subsidiary has to be sustainable for CIL to succeed. PSUs are scared of the five Cs: the central information commission (CIC), central vigilance commission (CVC), central bureau of investigation (CBI), comptroller and auditor general (CAG) and the courts. We cannot wish them away,” he says. To take away the fear of the five Cs, CIL is bringing in a lot of transparency using digital technology.

Greening the mined patches

Once mining is over in a patch of land, the next task is to restore it to its near-original form. Open cast mining is far more environmentally hazardous than underground mining. Environmental policies such as afforesting mined lands have been adopted right since the inception of CIL to mitigate the ruin caused by coal mining.

For every hectare of forest land acquired by CIL, the company has to pay the forest department double the price of the land which the department uses for compensative forestation. The project started with planting only trees. So far CIL has given Rs 800 crore to state forest departments. Niranjan Das, CGM, environment, CIL, says that ideally the subsidiaries should plant precisely those species of trees that grew in the area before mining but sometimes plans have to be altered due to local conditions.

Following a Ranchi high court judgment, BCCL since 2011 has been collaborating with the forest research institute (FRI) in Dehradun to restore the land to its earlier state, to the extent possible. FRI recommended three-tier plantation – grass, shrubs and herbs, and big trees – to start off the food cycle which will eventually attract insects and animals. The subsidiary has created an environment department which is engaged in the biological reclamation of the mined lands. The Gokul eco-cultural park covers a large portion of the mined-out area near the actively mined JCF. A team of gardeners are working on the park. “We route the ground water from the actively mined areas via pumps to nurture the eco-park,” says Raj Kumar, senior manager, environment department, BCCL. Originally from the desert state of Rajasthan, he knows how to utilise resources optimally.

Such rare patches of greenery also help the mining firm earn goodwill of the people. Coal mining in Dhanbad, the coal capital of India, is more than hundred years old. Before nationalisation of the coal mines in 1972, the coal mafia of Dhanbad had a free run exploiting the natural resource, degrading the environment and terrorising local people. PSUs took the place of the Mafiosi but in public imagination the link between coal mining and terror lingered on. BCCL could never break the ice with them. The hostility of locals was compounded at times due to land acquisition for coal mining. The Gokul eco-cultural park is an attempt by BCCL to bond with the locals.

“There are not many recreational opportunities in Dhanbad. The idea behind the park is to give the people some space to hang out,” says Raj Kumar. The park is dotted with fruit-bearing trees, and people are free to help themselves pick the fruits. “Inside the park, we relocated a temple which was situated on coal-bearing land. That also struck a positive note with the people,” he adds.

At Tetulamari in Sijua area of BCCL, 17 km from Dhanbad, when one looks at the thickly forested land it is difficult to imagine that this was a mined-out area a few years ago. Overgrown grass, varieties of shrubs and tall trees dominate the terrain where one would expect nothing more than barren swathes of land.

Since its inception CIL has planted 8,26,76,991 trees in a total area of 39,944.63 hectares. A portion of the biologically reclaimed land is turned into a water body. Rainwater is harvested to recharge the ground water lost during mining. To ensure that the coal mining behemoth does not renege on its environmental responsibility, they have to deposit money in an escrow account of the government (Rs 1 lakh per hectare for underground mines and Rs 6 lakh per hectare for open cast mines). Before mining begins, the subsidiaries have to prepare a mine closure plan. “If we do not close the mines according to the closure plans, then they will have the fund to restore the land to its initial condition. But if we follow the mine closure plan, then the government will return the money after third-party verification,” says Das.

The management set-up has been tweaked in CIL and its subsidiaries for faster progress. But the recent slump in economy has been a setback for the coal producer. It has been suggested that the rising stock of coal in power plants is due to decrease in power production. The growth in coal production is good news for CIL but unless power stations put that coal to use quickly, it degrades in quality. The industry has to stay a step ahead of CIL that is roaring to run.

(Source: http://www.governancenow.com/)