When mining interests prevail over SC order

Date: Aug 5, 2013

The apex court, last year, had mandated environmental clearance from the Centre for mining minor minerals that includes sand. Uttar Pradesh where IAS officer Durga Shakti got suspended after taking on politicians involved in sand mining is not the only state to bypass the court order. Reports by M Suchitra from Andhra Pradesh, Alok Gupta from Bihar and Aparna Pallavi and Akshay Deshmane from Maharashtra

.jpg)

Bank of Bankot creek in Mahad, Raigad, ravaged by sand mining (Photo by Aparna Pallavi)

Andhra Pradesh: stringent policy, only on paper

It seems the Andhra Pradesh government has not taken seriously the Supreme Court’s directions on sand mining. Large-scale illegal sand mining is reported from at least seven districts—Guntur, Krishna, Khammam, Waranagal, Srikakulam and East and West Godavari district.

Mining is happening in all the major rivers of the state—Krishna, Godavari, Vamsadhara, Penna, Pranahita and their tributaries. According to rough estimates, about 2,000 trucks of sand reach Hyderabad, the capital city, from Krishna district alone for the construction sector. Even at conservative estimates, sand worth R 1 crore is transported everyday from Krishna district. The rampant mining has led to acute groundwater crisis in the villages along these rivers.

The state has a stringent law in place to curb indiscriminate and unscientific sand mining—the Andhra Pradesh Water, Land and Tree Act (APWALTA), formulated in 2002. The main objectives of the legislation is protecting surface and ground water resources, regulating utilisation of water, protecting land and environment and prohibiting indiscriminate sand mining.

The legislation permits mining in streams and rivers where thickness of sand is more than eight metre. Here, the sand can be removed up to two metre. Mining is restricted where thickness of sand is below eight metre and above three metre. Mining is strictly banned where thickness of sand is less than two metre. Under this Act, it's illegal to mine sand near ground water structures, dams and bridges and other important structures. Use of heavy sand removing machinery is also banned.

Despite having a stringent legislation and a district-level committee with joint collector of the district as chairperson to monitor sand mining, all the rules are being flouted. A strong- nexus between the local politicians cum people’s representatives and contractors in connivance with the government officials continues to operate in the state. Even after frequent hue and cry over illegal sand mining, no one has been convicted so far under this law.

On 29 March last year, the Andhra Pradesh High Court had stayed sand mining and all other related activities in the state while considering a public interst litigation filed by K Koteswara Rao and Annam Sivaiah from Dharanikotta village in Amravati block of Guntur district against indiscriminate and unscientific sand mining taking place in the Krishna river. The court noted that illegal miners were operating hand in glove with government officials and that as a result of this unholy nexus a mafia-like situation had emerged in the state. The stay came into effect on April 1, 2012. The court rejected all the pleas by the state government to get the stay vacated (also see SC refuses to lift ban on sand mining in Andhra Pradesh).

The Andhra Pradesh government on May 7 pleaded before the Supreme Court that it was losing revenue because of the ban on sand mining and that several welfare schemes had been facing financial crunch. It has also maintained that construction works, both in the public and private sectors, have been hit hard by the stay. The Supreme Court directed the state government to approach the Union Ministry of Environment and the Forests (MoEF). As on September 24, 2012, the State Environmental Impact Assessment Authority (SEIAA) under MoEF has granted permission for mining in 71 sand reaches in four rivers—the Krishna, Godavari, Penna and Vamsadhara.

Lottery system not implemented

The State government announced new mining policy in September 2012. It decided to do away with the system of public auction of sand reaches based on tenders. Instead, a new system of drawing lots for granting the sand leases was to be introduced. The new policy was based on the recommendations of a seven-member Cabinet sub-committee of ministers led by minister for mines and geology, Galla Aruna Kumari. The state government appointed the committee on September 1, last year following uproar over rampant illegal mining even after the High Court stay. The government maintained that the new policy aimed at curbing illegal activities of the sand mafia in the state and making sand available for construction sector.

As per the new policy sand mining will be delinked from the Department of Mines & Geology and will be linked with Panchayati Raj department as it used to be till 2006. But the policy has not been implemented so far.

Interestingly, the new policy permits sand mining even in minor rivers and streams, and even in private farms along the riverbeds. Only farmers who own the sand-casted land will be permitted to quarry and sell it after paying seigniorage fee to the state government. Sand reaches in tribal areas must be allocated to the local societies through gram sabhas as per the Panchayat (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act or PESA with help of the Andhra Pradesh Mineral Development Corporation (APMDC) and Integrated Tribal Development Agency (ITDA).

The policy also insists that extraction of sand should be by manual means only and use of machinery has not been permitted except in specific sand-bearing areas where there is no impact on groundwater table. The state government has fixed the standard price for sand at the pitheads of sand reaches at R 325. The district authorities are to fix the selling price which should be not more than 20 per cent of the standard rate. The sand quarrying must be carried out only for the quantity fixed in the mining plan and it should not exceed the thickness stipulated in the APWALTA.

The Department of Mines & Geology's estimate of sand requirement for 2012-13 for constructions and civil works in private and government sectors was 2.18 million cubic metre and 230 cubic metre, respectively. Even now local politicians and big contractors dominate the sector.

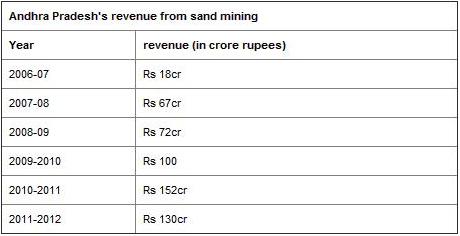

Till 2006-07, sand mining was under Department of Panchayati Raj. After that, the Department of Mines and Geology took over sand mining. Since then the revenue of the state from sand mining is steadily increasing (see table). The revenue comes from royalty, auction, temporary leases and fines for violating laws. Though the revenue figures go up with every passing year, unofficial estimates show huge loss to the exchequer because of illegal sand mining. On a rough estimate, about Rs 2,000 crore worth sand is quarried every year in the state.

Bihar: lawlessness rules

Bihar has witnessed a lot of bloodshed in the name of sand mining. In the past one decade, over 300 labourers have been killed in the fight to control sand mining.

Hench men of gang lords still ride on horse backs and SUVs along the Sone and Kiul Rivers to keep a control over their “undefined” mining area. In 2001, 11 labourers working for a higher caste gang lord were massacred on the banks of the Kiul river. There is constant gun battle in the nine divisional areas of sand mining in the state.

In 2012, in just one year, fight over sand mining has resulted in lodging of 1,920 FIRs, arrest of over 62 persons and raids conducted at more than 300 spots.

Even court orders have proved futile in the face of the deep nexus among politicians, gang lords and a section of government officials. Bihar has not implemented a single measure suggested by the Supreme Court to make the sand mining environment-friendly. Uncontrolled mining continues.

Mohammed Hasnain, joint secretary of the state mines and geology department told Down To Earth that complete lawlessness prevails in the state as far as sand mining goes. He said there are many instances when ministers have restrained officers from implementing the rules.

“Our ex-minister, Satdeo Narayan Arya had transferred 12 upright officers in 2012 in a bid to award mining tender to his henchmen. We protested his move,” Hasnain said.

The strong protest ruffled Chief Minister Nitish Kumar and he cancelled the entire transfer order.

Advocate Basant Chaudhary presents a different side of the picture—of those mining officials who are not so upright. Chaudhary had filed a public interest petition in the Patna High Court on indiscriminate sand mining in Banka and Jagdishpur areas of Bhagalpur district.

In his petition, the advocate gave evidence of how 40 to 50 natural water channels, the backbone of rice cultivation in the area, have dried up because of rampant sand mining. Rice cultivation had to be stopped in a total area of more than 1,500 hectares because the canal dried up.

The court ordered immediate stay on mining in the area and asked the mining department to file a reply. “They misled the court and this led to continuation of mining in the area,” Chaudhary said. The matter is still sub judice. The reply submitted in the court was prepared by senior officials of mining department.

While the government officials blame politicians, activists blame government officials for the prevailing rot.

Policy yet to be framed

The state mining department announced tenders for nine regional sand mining areas—Patna, Magadh Saran, Tirhut, Dharbhanga, Kosi, Purnea, Bhagalpur and Munger.

The tender is allotted to a single party who is the highest bidder. But there are no rules on how much area or how much sand is to be mined or what machines can be used to sand mining from the river bed.

“They can mine to any extent. Now, they even use heavy machinery like JCB to dig out sand,” said Hasnain.

Adocate Choudhary says sand mining has not only destroyed natural canals in Bhagalpur, there are many areas in the other districts that are facing similar problems. He says there is not a single study or survey on consequences of sand mining.

There have been reports that the railway bridge at Koelwar over the Sone river is also facing threat because of rampant sand mining. “The bridge’s pillar has suffered damage. The base of the pillar is nearly exposed due to heavy sand mining,” a senior administrative official said, claiming that a detailed report has been submitted to DRM, Danapur and the district magistrate of Bhojpur. Senior officials could not be contacted.

In February, 2013, former deputy chief minister, Sushil Modi, who also held the portfolio of environment ministry had announced that new sand mining policy would be prepared in the subsequent five months.

The minister’s deadline for drafting new policy in accordance with the Supreme Court directions expired last week. The sand mining policy has not been prepared as yet.

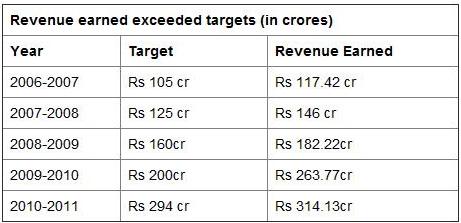

Sand mining gives the highest revenue of Rs 9,080.50 lakhs to the mining department. It’s also one of the departments in the state that has far exceeded it’s own revenue target (see table).

Dinesh Mishra, a river ecology expert in Bihar said when the state is getting such a high revenue from sand mining, it should show some consideration towards the environment also.

Mishra pointed out that Bihar produces two kinds of sand—coarse sand and fine sand. The former is the revenue spinner and also cause for massacres of both humans and the environment.

“Sand retains water and it keeps the river healthy. There should be scientific specification for mining the quantity of core sands. It cannot go uncontrolled,” he maintained.

In recent years, sand mining has started affecting embankments. Heavy machinery is used and the large-scale mining of sand in Champaran. Residents lodged a complaint with the mining department and the police chief about the damage to embankments, but there was no response.

Residents then formed an Embankment Protection Committee and jointly filed a petition against sand mining along the Gandak river in the Patna High Court. The matter is subjudice.

The inaction of the state government in curbing illegal sand mining has earned it bad reputation. University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Advance Study of India presented a lecture by Jeff Witsoe at a seminar. He highlighted that the sand mafia in Bihar is increasing despite claims of better governance in Bihar.

Maharashtra: mechanised mining replaces manual mining

The Supreme Court’s February 2012 order, making Environment Impact Assessment mandatory for mining of minor minerals, is being observed more in violation than in observance in Maharashtra. On the one hand sand mafia has come up with innovative techniques to skirt the law, on the other, the bureaucracy has paved the way for them by failing to complete the measuring and demarcation of sand mining blocks.

Take the instance of Nagpur district. Since 2011, the Nagpur office of Maharashtra’s Ground Water Survey and Development Agency (GSDA) has not issued any permission for mechanical sand dredging in the district. This information was found by city-based RTI activist Paramjeet Singh Kalsi. A former transport businessman who used to transport sand from mining sites, Kalsi recently filed a public interest petition with the Nagpur bench of the Bombay High Court against irregularities and violations in sand mining laws and regulations in the Nagpur and Bhandara districts. “Mining without GSDA’s permission is not possible,” he said. “Yet mining is going on using machinery in the open at more than 200 places in the district.”

The how of it is rather simple. “All the mining is happening in manual mining permits,” he said, “since EIA is required only for mechanical dredging.”

A similar situation can be witnessed at Bankot creek on the border of the Raigad and Ratnagiri districts in western Maharashtra. “Contractors get permits for manual excavation, but then they install suction pumps,” said Nasir Jalal of the non-profit Citizens for Justice and Peace based in Mahad tehsil of Raigad district.” The use of pumps is not permitted in sand mining at all, but authorities are simply looking the other way since they are not using dredgers, for which EIA is required.”

Jalal, along with Sagar Shramik Haat Pati Vaalu Utpadak Sahakari Sanstha, a Mahad-based union of manual sand excavators, was instrumental in getting the Maharashtra government to frame its October 2010 sand mining policy which makes gram sabha consent a must for mining.

Mumbai-based Sumaira Abdulali of the non-profit Awaz Foundation, who had filed Maharashtra’s first court petition against illegal mechanized dredging, said that the order has not been implemented at all. “In coastal Maharashtra the Maharashtra Maritime Board is responsible for granting mining permits as well as demarcating the mining blocks, but more than a year since the order, the body has not succeeded in so much as completing the measuring and demarcation work.” EIA will not be possible unless this work is done, she said.

Government resolution legalizes irregularities

A resolution of the Maharashtra government dated March 12, 2013 has made it easier to get mining clearance. Diluting the norms of the Coastal Regulation Zone Act 1991, which bans all sand mining in coastal areas except for channel clearing, the GR has drawn up two criteria for determining the quantum of mining, the first is mining to clear river beds and creeks for navigation, and the second, to maintain enough sand stocks for the requirements of the building industry. “This new criterion is a blow to sustainable sand mining,” said Abdulali. “The amount of sand generated by waterway-clearing will never be sufficient for the construction industry, and additional mining permits will have to be given, which will simply continue to damage the environment. It is in effect legalising existing malpractice.”

The state’s 2010 sand mining policy had sought to include the gram sabha in the decision-making process of allotting leases, but the latest GR cuts down the earlier one month deadline for community decision to 15 days and puts the onus for finding a “good reason for refusal” on the gram sabha itself. The Maritime Board is also required to give its survey report in ten days. In both cases, failure to meet the deadline will mean “deemed clearance”. “This is in effect giving a free-rein to the mining contractors and the corrupt revenue department it is in cahoots with,” said Jalal, “In Mahad, villages on the banks of the Bankot creek have been opposing mining for years, but the contractor-official nexus manages to get clearances in the teeth of opposition.”

The GR has also diluted the provision for not allowing suction pumps for sand excavation by making their use permissible under circumstances where manual and mechanical dredging is not possible or to prevent floods. “This provision will be misused to permit suction pumps to skirt EIA requirements,” said Jalal.

Political maneuvers

As in the case of Uttar Pradesh, political support for illegal and unrestrained mining in Maharashtra has ensured that it not only survives but thrives. Politicians are making relentless efforts to get their way around any efforts at putting a leash on questionable mining practices.

Chief minister’s balancing act

While writing to environment minister Jayanthi Natarajan about the probems posed by the Supreme Court order, Chief minister Prithvi Raj Chavan attempted to strike a balance just so that he does not to appear to be against the Supreme Court order. Chavan recommended that the industry be exempted from the mandatory environment clearance only for one mining season. He argued that the rules could begin to be implemented from the next year’s season, beginning September 2013, as this would give sufficient time to “the project proponents and the district administration to gear up the machinery to meet all the procedural requirements as per the EIA notification.”

Chavan, who is widely regarded as a clean administrator and politician, had another recommendation. He was of the opinion that since many of the mining blocks below 5 hectares are in small pockets of 1, 2, and 3 hectares, clubbing together of all into the below 5 hectares category required to be “reexamined” and clearances not be made mandatory for those spread over an area up to two hectares until September 2013.

It was Chief Minister Prithviraj Chavan himself who began lobbying with the Union environment minister Jayanthi Natarajan in the interest of the mining industry. In his letter sent to Natarajan in October 2012, Chavan cited the “enormous practical and procedural difficulties” in following regular environment clearance norms, as mentioned in the Environment Impact Assesment (EIA) notification of 2006, which had severely affected the mining industry. “The Hon’ble Supreme Court has put the block below 5 hectares also in the same category as those above 5 hectares. Needless to say such a step would lead to extraordinary delays in sanctioning of mining leases/renewal. This step has brought the entire mining sector to a standstill,” he wrote (see box).

The real estate sector and state’s revenue department also had their own reservations about the SC order. The construction industry complained of delays in getting raw material and clearances while the revenue department expressed dismay over drop in revenue.

Facts contradict Chavan’s alarmist claim about the entire mining sector having been brought to a standstill because of the Supreme Court verdict and subsequent MoEF actions. Estimates presented by the state in its Economic Surveys for 2012-2013 and 2011-2012 show that the condition of the mining sector is not going downhill. While the sector saw -5.5% growth in 2011-12, it improved to -1.9% in 12-13. The quantity of minerals manufactured improved marginally in the case of minor minerals and considerably in the case of major minerals. Interestingly, even as the revenue department was talking of a drop in revenues, the surveys admitted to not recovering at least Rs 310 crore till 2010-2011 from the extraction of minor minerals. Of this amount, Rs 222 crore is under dispute. No explanation is provided about why the remaining Rs 88 crore was “raised but not realized”. Despite repeated attempts, revenue department officials could not be reached for comment.

Subsequent to Natarajan’s unfavourable response and direction to the state about following the EIA notification norms in January 2013 and the Mumbai High Court’s parallel orders to that effect, the state updated its sand mining policy in March 2013. But it is still to finalise a policy concerning the mining of minor minerals. This, when the latest sand mining policy has been criticised by campaigners and increasing instances of political pressure on experts responsible for screening projects for environment clearance is being witnessed.

Experts protest

Among the most striking developments related to this was witnessed last month when the State Expert Appraisal Committee (SEAC-1) resigned en masse in protest against strong political pressure. Among the many reasons it cited for the resignation, one was pertaining to the serious problems relating to minor minerals. In his letter of resignation, former NEERI director and chairperson of SEAC-1, Sukumar Devotta said: “With the advent of SC Order on Minor Minerals, the pendency list increased substantially. Even though there was a draft Maharashtra Policy of Mining of Minor Minerals (MoMM), this has been pending for a long time. SEAC1 visited a few sites on 13th Feb 2013 to understand the ground reality. We also requested DMOs (District Mining Officers) to bring all cases at one go so that SEAC could handle the MoMM cases in time to meet the deadline specified by SC Order. However, most of the cases were brought before SEAC1 repeatedly without proper survey, data and approvals. Such cases were repeatedly included in the agenda without looking into the genuineness and completeness of the proposals due to political pressure and demand for materials. This made the appraisal by SEAC1 extremely difficult and frustrating for all involved. In some cases, recently SEIAA had issued EC even before the cases were appraised by SEAC1. The whole process has become a farce and SEAC1 is blamed for all the delays.”

Explaining why minor minerals are a far bigger environment concern, a member of this committee told Down To Earth: “Mining of minor minerals is far more hazardous as they are scattered all over and there is no implementation of environment management plans. The damage to environment is thus, permanent and irreversible. And yet, there was too much political and administrative pressure for quick clearance of projects.”

Expectedly, the administration does not appear to be seriously inclined to arrest this process. Abdulali of Awaaz Foundation, said: “The Sand Mining policy has for the first time said that mining is permitted by the administration primarily for making sand available for developmental purposes. The fact of having the sentence there makes the intention of the government clear. It is not counting costs to the environment.”

(Source: http://www.downtoearth.org.in/)