Envis Centre, Ministry of Environment & Forest, Govt. of India

Printed Date: Wednesday, January 7, 2026

Topa Colliery on 16.7.1982

Topa Colliery

| Date of the Accident |

- 16.7.1982 |

| Number of persons killed |

- 16 |

| Owner |

- Central Coalfields Ltd. |

| Place |

- Kuju Area, Hazaribagh District, Bihar |

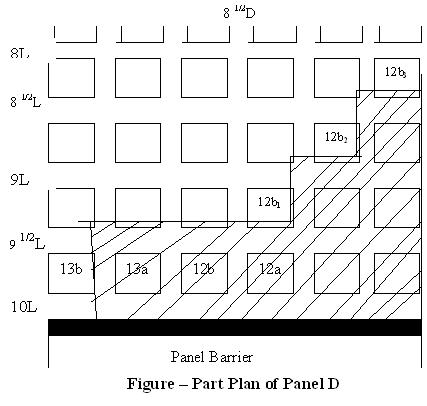

This accident had caused the largest number of deaths due to a roof fall in coal mines in India. The accident occurred in Panel D, the only depillaring district, of VIII B seam which was worked through 2D Incline. In the said panel, the seam was 2.58 m thick and had a gentle but varying dip in more or less northerly direction. The depth of cover was less than 15 m. The immediate roof consisted of a band of shaly sandstone of thickness 5 cm to 30 cm and was overlain by alternate layers of grey shales, fine-grained and medium-grained sandstones. The shaly sandstone layer comprising the immediate roof when exposed, had a tendency to part easily from the rocks above, especially where the galleries had become wide. During depillaring, the immediate roof, ranging in thickness upto 30 cm, used to come down within a day of withdrawal of supports except near the panel barrier, where it used to come down in 2 to 3 weeks time. The main fall of the roof above, extending upto the surface, used to occur in 2 to 3 days except near the panel barrier where it took 4 to 6 weeks time.

The seam had been developed before nationalization and at the time of the accident, depillaring was being in Panel D. In the year 1980, the management had applied for permission to depillar Panel A and Panel B (Subsequently named Panel D). After discussion with the management which was facing difficulties in providing work to loaders, permission was granted to extract Panel A with the tacit understanding that such permission would not be granted for Panel B as the depth of cover was less than 15 m. Even so, the management applied for depillaring permission for panel D in October, 1981. But without waiting for the permission, the management commenced depillaring in Panel D in January, 1982. The General Manager wrote to the Chief Inspector in March 1982 requesting for grant of depillaring permission for Panel D explaining that the management was facing the problem of employing persons after the extraction of Panel A had been completed. The mine was inspected in May, 1982 and conditions were found to be generally satisfactory but the Inspectorate was annoyed on discovering that depillaring had already been started. Therefore permission was withheld until the management explained the exigencies of the situation and promised never again to start depillaring without obtaining the requisite permission. The permission for depillaring in Panel D was finally given in June 1982 with the following stipulation:-

- Each pillar to be divided into 4 equal parts by level and dip split galleries not more than 3.5 m wide.

- Each stook to be extracted in half-moon fashion leaving 2 m thick rib against the goaf which may be reduced judiciously on retreat.

- Not more than 61 m2 of roof to be exposed at any working place.

- Heightening of split or original galleries to be done immediately before the commencement of extraction operation.

- Extraction to be commenced from dip-most side to rise-side maintaining a diagonal line of extraction and avoiding formation of ‘V’ in the line of extraction.

A copy of the Systematic Support Rules framed under CMR-108 accompanied the permission granted. According to para 7(1) of these Rules, cogs were required to be set alongside the ribs of coal left against the goaf at intervals not exceeding 2.4 m.

During the inquiry into the accident, it was revealed that pillars were extracted without leaving any rib against the goaf and no cogs were erected alongside the ribs as required by the Systematic Support Rules.

Events preceding the accident:

In the first shift of 16.7.1982 (8 a.m. to 4 p.m.) the Mining Sirdar instructed the shotfirer to blast stook No.12b1. (In all, 12 holes, six on each side, were blasted. As a result of the blast, the supports near the stook were disturbed. The cogs near the goaf edge and junction of 81/2 dip and 9 level were also dislodged. The shotfirer got 2 new props set at the 9th level goaf-edge and re-set the cogs and props near the junction, He had, however, not re-set the goaf-edge cog at 81/2 dip. When the Mining Sirdar reached the place, he sent away the shotfirer for blasting other faces in the, 7th level. At about that time, 3 gangs of loaders, 30 to 35 in number, who had earlier been directed by the Mining Sirdar to proceed to the 9 level stook, arrived there. They loaded one rake of 8 tubs, supplied at about 1 p.m., from the blasted coal lying there. These loaded tubs were hauled out and shortly afterwards, at about 2 p.m., another set of 14 tubs was made available in the 9th level. But the coal available at the stook was only 4 to 5 tonnes, and 6 to 7 tonnes of coal had been thrown by the blast into the standing unsupported goaf of stooks 12a and 12b. The goaf-edge cog at 81/2 dip below 9 level had not been re-set, as mentioned earlier.

The accident:

The Mining Sirdar asked the loaders to collect the coal lying scattered inside the unsupported goaf and load their tubs. Some of the loaders hesitated; others protested, saying that they would not like to take the risk.

But the Mining Sirdar himself went into the goaf and stood there saying that the roof had not come down so long and was unlikely to fall in about 15 minutes or so in which time the scattered coal could be collected. To some of the workers he said that if they did not do so, they would not get their fall-back wages. To others he said that if they did not obey his orders, they must leave the mine. Seeing the Mining Sirdar himself standing inside the unsupported goaf, some of the loaders ventured into the goaf and started collecting the scattered coal. Others too then followed and did likewise. The loading work had thus been going on for about 10 minutes when, at about 2.45 p.m., all of a sudden and without any apparent warning, a large mass of the immediate shaly-sandstone roof came down from the unsupported goaf and fell over the workers. 15 loaders and the Mining Sirdar died in the accident and 4 loaders received serious bodily injury.

The causes of and the circumstances attending the accident:

The roof of the goaf was wholly unsupported because all the supports had been withdrawn there-from about two weeks earlier. The roof was left to fall like other similar roofs. It was intended that it should fall. Only the precise time of its fall could not be predicted. In view of the anticipated fall and the danger arising there-from, the Mining Sirdar was bound to get the goaf edge securely and effectively fenced. Not only he failed to get that done, but he actually directed the timber-mistry and timberman not to do so. Secondly, the Mining Sirdar was bound to prevent the loaders from entering into the unsupported goaf where they were likely to be endangered; but contrarily, he almost compelled them to go and work there. Thirdly, the Mining Sirdar himself should have refrained from going into that prohibited area and thereby endangering his own life; but once again the flagrantly violated the requirement of the relevant regulation. Thus the accident is directly attributable to the action taken by the Mining Sirdar in trying to collect the coal scattered in the unsupported goaf in 81/2 dip adjacent to the stook under extraction. This then is the main cause of the accident.

Although the loaders had protested against the order requiring them to collect coal from the unsupported goaf, but eventually they all went to work in the goaf after they were cajoled, persuaded and threatened by the Mining Sirdar. Unfortunately, none of them was strong enough to refuse to carry out the illegal orders of the Mining Sirdar although they were aware of the possible consequences. If only they could have taken courage to do so, they would have averted this major disaster. To this extent they too contributed to the causing of the accident.

The role of Overman:

As the Shift Overman of Panel D was on leave, the Acting Manager had appointed another overman to work as “Shift-cum-General Shift Overman” for the whole week.

It is odd that an experienced man like the Acting Manager passed such an order in disaccord with CMR -43(8) which requires the Shift Overman to devote the whole of his time to his shift duties and not to leave his district except for a justifiable cause (which must relate only to his duties enumerated in CMR-43).

On 16.7.1982, the said Overman was present belowground from 9 a.m. till 12.30 p.m. He then went to the surface, purportedly to arrange for repair of the surface track and supply of tubs to 9 level, and returned to the belowground workings at about 3 p.m., that is, only after the accident.

If the Overman was present in the district, he could have intervened on behalf of the loaders who had protested against being required to work in the prohibited area and, in all likelihood, the Mining Sirdar would not have ventured to act as he did. Even otherwise, the Overman being an official superior, could have acted on his own under CMR-43(3)(c), and sent out of the mine the Mining Sirdar and the loaders endeavoring to work in that prohibited area and thus averted the accident.

The role of supervising personnel:

When the proper working of a mine is overseen and controlled by a hierarchy of officers, it is the duty of the management to ensure, lest the safe working of the mine be jeopardized, that the supervising officers at several levels are not simultaneously unavailable. On the date of accident, the Manager was acting as Agent and the Assistant Manager was the Acting Manager. The Safety Officer had been transferred and his successor had not taken over. The Overman was on leave and the one who took his place was “Shift-cum-General Shift Overman”. Thus at the material time, supervision of the district was wanting at two successive levels, and was ineffective at the third successive level. It has-been shown how the Mining Sirdar, in spite of protests from loaders, compelled them to work in a prohibited area. The Overman, having gone out of the 2D Incline, remained on the surface and was unavailable at the critical time for intervention. The Acting Manager, on getting the news of the accident, when he was near the MN Incline, became perplexed and, instead of going into the mine to help the victims, left the place saying that he would reach 20 Incline within minutes. Ultimately, he could not reach the site of the accident before 22.7.1982. The conclusion cannot be avoided that at the material time, the mine suffered from lack of effective supervision. On behalf of the management, great stress was laid on the leave requirements of supervisory personnel. It should be emphasized that grant of leave must be so adjusted as not to affect the safe working of a mine and that, in the last resort; leave may well be refused if proper supervision required for safety is likely to be affected.

Recommendations:

From the evidence laid in this enquiry, the Court found some undesirable features connected with the day-to-day working of the mine. Extraction of pillars was commenced without obtaining the requisite permission from the DGMS. Though a formal permission was received shortly before the accident, pillars continued to be extracted as before, without giving due importance to the conditions laid down in the permission. A clear-cut appreciation of the purpose of diagonal line of extraction and of leaving ribs of coal against the goaf during stook extraction was wanting at all rungs of the management. The Overman remained on the surface too long. There was, indeed, a general atmosphere of lack of safety consciousness and the management considered it sufficient for them to prove that they had complied with the regulations dealing with safety and the directions of the DGMS in relation thereto. It should be emphasized that the management is primarily responsible for safety in mines and they have to take on their own all possible precautions and not merely those contained in the regulations or directions of DGMS. Similarly, in regard to production it was found that the number of loaders had been much more than what was required from the point of view of production or safety or capacity of haulage system or availability of tubs. The need of having to pay a large amount of fall-back wages for a long period did not caution the management. In the opinion of the Court, just as the management cannot claim to be concerned merely with production, so also the DGMS should not take the view that he is wholly unconcerned with either production or cost. Taking this comprehensive view and thinking that this appraisal of the situation applied to most of the coal mines, the Court made the following recommendations:

- There should be for each Area an Area Planning Officer assisted by staff adequate for his requirements. Once the target of production from any mine in the Area is fixed, it would be his duty to do detailed planning to achieve the target. His planning should include lay-outs of panels, arrangements for extracting coal from faces, haulage, support system, ventilation, coal dust suppression, manpower, management of supply of materials required, and safety arrangements, including precautions against air-blast, fire and inundation, traveling roads and emergency second outlets. A detailed report will be prepared for each mine in the Area, indicating, the officials charged with execution. The report should then be discussed with the General Manager, Agent and Manager of the mine. After finalization and approval, it would be signed by all these officials and would not be modified or departed from except with the approval of the General Manager.

- There should be an internal safety wing for each company headed by General Manager (Safety) and having at the mine level a Safety Officer. There should be sufficient number of Inspectors, each in charge of an Area, under the General Manager (Safety). The safety hierarchy should be subordinate to Technical Director, if any, or to the Chief Executive of the Board of Directors and not to the General Manager, Agent or Manager or to any officer working on the production side. The role of the Safety Officer should be advisory and not executive. For example, he may point out the shortcomings from the safety point of view to the manager and if he is dissatisfied with the response, he may report to his own superiors in the hierarchy. It will be his duty to report to his superiors the existence of unsatisfactory safety conditions, if any, found in the mine in his charge. It appears that, at present, such independent internal safety wing does not exist in the Central Coalfields Limited because the Safety Officer of Topa Colliery had been required to look after production work.

- Although workers’ association or participation in the management of a mine is still a far cry, I would nevertheless suggest that a nominee of the workers should be associated with safety arrangements made for every mine. The institution of Workmen’s Inspectors in mines, as recommended by the First Safety Conference (1958) was not given, effect to even after nationalization. It may be pointed out that Workmen’s Inspectors have been appointed in other countries like U.K., France, Belgium, Turkey, U.S.S.R. and their work has been found to be useful. Regular inspections by Workmen’s Inspector, who commands the confidence of workmen, is likely to supplement the action taken by the Director General of Mines Safety and the Internal Safety Organization and so provide better safety for workmen. It is, therefore, recommended that early steps should be taken to appoint a Workmen’s Inspector for every mine.

- After nationalization of coal mines and development of the mineral industry, there appears to have been an erosion of the authority of the Directorate-General of Mines Safety for various reasons, including failure to adequately strengthen the directorate to meet the needs of the changing situation and difficulties in recruitment of officers. The question had been discussed in various forums, including the Fifth Mines Safety Conference (1980). Subsequently, Government of India appointed in 1981 Kumaramangalam Committee mainly to review the role and functions of the Directorate General Mines Safety with reference to changes and developments in mining industry. That Committee has already submitted its report, which is under the consideration of Government of India. While the action taken on the report may not be anticipated, it must nevertheless be stressed that the Directorate General of Mines Safety must continue to be the authority for enforcement of all statutory provisions in mines and its authority should be improved so as to give it the same status which it had before nationalization, For this purpose, the Director General of Mines Safety should be given the status of Additional Secretary to Government of India, the staff strength of the Directorate should be enlarged to enable it to satisfactorily fulfill all the obligations in the changed circumstances and the service conditions in the Directorate should be improved so that qualified and competent persons continue to serve in the organization.

- There is general shortage of statutory mining personnel. The Director General of Mines Safety has reported that there is a shortage of 147 First Class Mine Managers, 65 Second Class Mine Managers and 153 Mine Surveyors in coal mines. These estimates dated 23rd May, 1983, are based on the information available on the basis of the present statute framed prior to nationalization of coal mining industry. With the opening of more widespread wings of the coal mining industry for better management, the real shortage is likely to be larger. This state of affairs cannot be allowed to continue for long and it has now become very necessary that the coal mining industry itself takes up the task of imparting necessary education and training to meet the requirements. It is therefore recommended that prompt attention should be paid to this aspect of the matter and early steps taken so that the industry does not suffer from want of persons competent to discharge managerial responsibility.

- This accident, which caused the largest number of deaths by fall of roof in the history of coal mining in India, is a matter of public importance. Lest passage of time erodes the importance of such accidents, it is desirable that any Court of Enquiry constituted for such cases acts and reports quickly. This is all the more so because until the Court of Enquiry inspects the site of accident, the mine remains closed, there is no production from the mine and the miners working there remain unemployed. It is, therefore, recommended that whenever it is found necessary to appoint a Court of Enquiry, the notifications for appointment of the Court of Enquiry and setting up machinery therefore should be issued simultaneously and a time limit should be fixed for submission of the report.