Envis Centre, Ministry of Environment & Forest, Govt. of India

Printed Date: Sunday, July 20, 2025

Jagannath Opencast Project on 24.6.1981

Jagannath Opencast Project

| Date of the Accident |

- 24.6.1981 |

| Owner |

- Central Coalfields Ltd. |

| Number of persons killed |

- 10 |

| Place |

- Talcher Coalfield, Orissa |

At about 1 p.m. on 24.6.1981 a very unique kind of accident occurred at Jagannath opencast mine when a large quantity of hot ash and dust was ejected from the southern side of the quarry and was spread over a wide area. Fourteen workers, then present at a distance of about 60 m from the south quarry face, were engulfed in a cloud of ash and were severely burnt. Ten of them succumbed to their injuries within a few days while the remaining four survived with serious injuries.

This incident is the only one of its kind in this country and, as far as is known, it has no parallel anywhere else in the world. Because of the uniqueness of this accident, the Court of Inquiry decided to have the matter investigated thoroughly by scientists from CMRS and CFRI. Unfortunately, however, the Court and the scientists could make the first inspection of the site only after about 6 months of the occurrence when most of the field evidence was lost. The court’s analysis was therefore based on facts brought out in the reports of the DGMS and the management and the evidence of the witnesses.

The mine

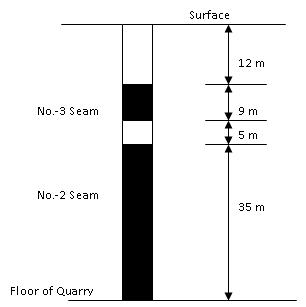

Jagannath Colliery had two quarries, namely, the Pilot Quarry and the Main Quarry. The accident occurred in Pilot quarry which was located in the trough of two strike faults running east-west. The strata dipped at 40 to 50 in northerly direction. No.3 seam was 9 m thick and occurred at a depth of about 12 m. No.2 seam (also called Jagannath seam) was about 35 m thick and occurred 6 m below No.3 seam. The quarry was worked with draglines, shovels, pay loaders and dumpers and was 52 m deep.

The accident

Prior to the accident there was heavy rainfall for 4 days. Between 20th and 23rd June a total of 162 mm of rain had been recorded. A pump was being installed on the quarry floor and the foundation job for this pump was awarded to a contractor who had engaged 3 workers including 5 females for the work. A civil supervisor, a pump operator, a mechanical fitter and the contractor himself were also present around the place. At about 1 p.m. when some of them were coming out of the pit for lunch, they heard a noise of rolling stones coming from the south side. When they looked towards the south, they saw a stream of stones rolling down the south side from a height of about 5 m above the quarry floor. As they started running towards the haul road, they felt that the sound of the sliding material was increasing and then they noticed a dense cloud of smoke and dust over their heads. The workers started shouting for help and water. Some of them reported seeing stones falling around them. The noise was described as “whoa-whoa” as if some gas was being ejected through a small opening.

An Executive Engineer and an Overman, present at different places on the surface at the time of the accident, saw a big cloud of smoke and dust coming up from the Pilot Quarry but neither of them heard any noise. The Engineer suspected that the dragline had caught fire. He immediately rushed to the Time-office in his jeep to collect some engineering personnel and with them he went into the quarry. According to the Engineer, the cloud of dust persisted for about 10 minutes. On the way he met some, workers staggering out of the quarry while others were lying down. Their bodies were covered with dust. All these workers had burn injuries with the skin hanging loose at many places. The clothes they were wearing were partly burnt. The Overman in the meantime came in a truck. They immediately arranged to lift the injured in the jeep and the truck and sent them to the Regional Hospital at Talcher Colliery, about 8 km away. At the, hospital they were given proper treatment. Help of specialists from other nearby hospitals and from the Medical College at Cuttack was also procured.

Four of the injured persons expired on the same day. One died on the 25th and another on the 26th. Three more persons expired on 29th, 30th June and 1st July bringing the total to 9. The 10th person expired on 4th July. All these persons had 80% to 100% bum injuries. The remaining four had less burn injuries and they survived.

After the accident the quarry bed was found covered with ash and clinker, which had spread in a fan-shaped area with an arc length of 210m and a radius of 90 m. The thickness of the ash varied from 0.5 cm to as much as 25 cm and the clinkers, 6 to 8 cm in size, were scattered upto a distance of about 60 m. There was a 4.5 m high coal heap 18 m away from the toe of the bottom-most bench. The valley-like portion between the coal heap and the bottom bench was found filled with a good thickness of ash, large-sized burnt stone pieces and boulders thrown down from the top of the quarry.

Conclusions from the DGMS inquiry

There was a slide in which about 800 tonnes of material came down along the south side over a width of about 20 m. This slide might have been caused by fire, heavy rain, presence of fault-plane, water entering through wide cracks on the surface, etc. or more probably by a combination of these. But the slide alone could not have thrown 6 to 8 cm pieces upto a distance of 60 m or so. Moreover, the scattered material was thrown from places which were on fire. Therefore there must have been an outburst also. As to the cause of the outburst, the most probable appeared to be an explosion of water gas (a mixture consisting mostly of H2 and CO).

The Management’s view

The management’s findings were more or less similar to that of the DGMS. They concluded that there was a slide on the southern side as well as an outburst and that the slide occurred prior to the outburst. However, they claimed to have seen at least one piece of stone weighing about 1.5 kg thrown to a distance of nearly 130 m from the site of the slide. As regards the cause of the outburst also their conclusion was the same; that is, the outburst could have occurred due to water gas explosion only. The possibility of high pressure steam being generated was ruled out because the pressure developed could not have been high enough to throw clinker and stones over such larger distances. The possibility of coal dust explosion was also ruled out because the heavy rain in the previous four days had completely saturated all the coal dust with water.

The water gas must have formed in the void created by the burning of the coal seam, and air entering the fire area must have rendered the mixture explosive which was ignited by the burning coal. Only the explosion of water gas could explain the degree of violence witnessed in this case.

The case put forward by CMRS

Like one of the Trade Unions, CMRS first considered the possibility of the incident having been caused by a simple slide. They assumed 24 m thickness of coal to have burnt completely reducing the original volume to one-third (as the ash content in coal varied form 30 to 35%). Assuming all favourable conditions, the velocity of the sliding mass could not have exceeded 18 m/s. Then assuming that any clinker might have attained this initial velocity, the maximum throw of a projectile at an angle of 450 would come to 33 m only. Therefore, the scattering of stone pieces beyond 33 m could not be justified by simple sliding and projectile ejection. They, therefore, concluded that there was an outburst also.

In trying to find out the cause of the outburst they considered the following possibilities:-

- Accumulation of methane along the fault plane and its explosion.

- Production of inflammable gases and methane by distillation of coal and their explosion.

- Coal dust explosion

- Hydraulic stimulation of crushed and permeable coal seam which may increase gas outflow upto 20 times.

- Generation of steam which could mechanically eject the ash and clinkers.

Scientific analysis of all factors eliminated these possibilities. Last of all, they discussed the possibility of water gas explosion and considered it probable. According to them, hot water and steam may pass over burning coal and change into water gas. Small amount of this gas with wide explosive limit (5-70%) may explode deep in the cut created by the fire and initiate scattering of the burnt ashes and clinkers over a fan-shaped area as reported by witnesses.

The colour of the smoke in this case will be grey (like that of ash), violence will be less severe but overall temperature of the bed of already heated ash will then rise because of its exothermic reaction. This seems to justify the burning of victims even at 90 m distance without excessive violence, smoke or sound.

The case put forward by CFRI

CFRI did not take into consideration any possibility other than explosion of gases. Their contention was that the smouldering fire in the seam might have been gradually covered up by self-generated ash and cinders and subsequently further blanketed by a huge amount of rock debris falling from the top. Heavy blanketing of the fire zone might have led to a number of chemical reactions in the coal-bed, namely, combustion, gasification and carbonisation, all of which culminated in the continuous generation of gases which might have built up a tremendous pressure deep within the fire zone. Eventually, when a critical pressure was reached, the cover of rock debris was thrown out creating an opening through which air rushed into the gas zone and caused an explosion of inflammable mixtures of CH4 air, CO-air and H2-air. Such an explosion, deep within the fire zone, had perhaps led to the sliding of enormous quantity of rock debris and the shooting of very hot spent gases accompanied by hot ash and cinders.

Commenting on the CFRI report, the management argued that if the gases produced by pyrolisis of coal not escape, it follows that no air could enter such a zone. Therefore the coal burning would have stopped and the fire would have died out in course of time.

The Court did not consider the case put up by CFRI as a probability.

The Court’s analysis

The Court based its analysis on the following three facts:

- A clinker weighing 1.5 kg was thrown over a distance of 130 m. The pressure required to do this would be about 350 p.s.i. Such a high pressure could not have been developed by a gas explosion.

- About 250 tonnes of material was thrown over a distance of 250 ft. The kinetic energy required to do this would be 17.9 mil Btu.

- “Whoa-whoa” sound was heard immediately after the incident.

The Court contended that in the circumstances prevailing at the time of the incident, there was a possibility of generation of superheated steam at high pressure. The heavy rain on four days prior to the incident could have clogged the cleavage planes and other natural fissures in the coal and associated rocks and steam superheated to about 800°F could be entrapped at pressures of 350 p.s.i. or more in the interstices of ash and strata. CMRS had not considered superheated steam and its entrapment in interstices of ash. Superheated steam can explain the high pressure required in this case and confinement in interstices explains how a large volume of steam could be stored. The “whoa-whoa” sound is explained by the escape of steam after the initial outburst.

It appears that a slight movement in the coal face was the fore-runner of the outburst and large scale slide of the side occurred only after the ejection of material from within the fire zone.

Conclusion

The incident could have occurred by a combination of circumstances. Probably high-pressure steam confined within the fire zone played the main role in the ejection of hot ash and cinders. But the contribution of other factors, such as the explosion of water-gas, cannot be ruled out.

This incident is a pointer to the grave danger that a blazing fire in a coal bench of an opencast mine can bring about. It is therefore necessary that such fires must be quenched as soon as noticed.

Recommendations

- The Regulations only specify that the occurrence of a fire in an opencast mine should be reported to the DGMS but do not say what the DGMS should do thereafter or the mine management should do on its own. The Regulations should be suitably amended to specify clearly the steps to be taken by the DGMS and the management.

- In an opencast mine as soon as a fire is noticed, it should be dug out and quenched. Alternatively, measures should be taken to prevent its spread by not allowing access of air to the fire; for example, by blanketing. In no case should mining operations proceed to such a depth, as in the case of Jagannath Colliery, that the management can claim that the fire cannot be tackled. Such a situation should not be allowed to develop. If the fire is not controlled, further mining operations in that quarry must stop.

- The phenomenon of spontaneous heating and the measures to deal with fires in opencast mines need to be investigated thoroughly by a High Power Body which should evolve guidelines for the industry to deal with the problem.