You are here :

Home Gaslitand Colliery on 26 or 27.9.1995

|

Last Updated:: 02/06/2015

Gaslitand Colliery on 26 or 27.9.1995

Gaslitand Colliery

| Date of the Accident |

- 26/27.9.1995 |

| Number of persons killed |

- 64 |

| Owner |

- Bharat Coking Coal Ltd. |

| Place |

- Jharia Coalfield |

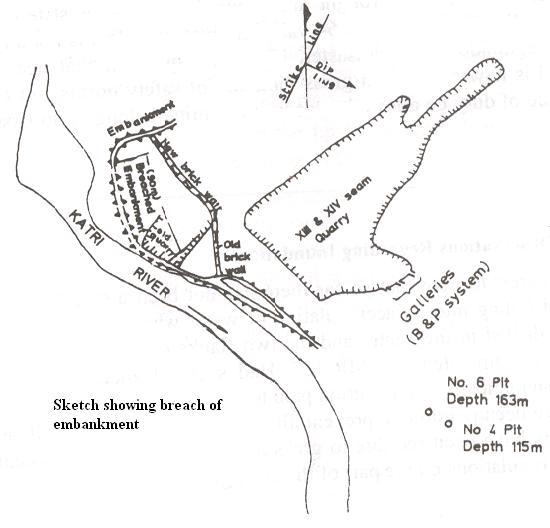

Rising water of the flooded Katri River breached its embankment and entered underground workings through galleries exposed in the worked out quarry. Gaslitand mine, situated on the bank of Katri River, is one of the oldest mines in the Jharia coalfield, having been started in 1896. The present Gaslitand Colliery was formed by amalgamating Union Angarpathra Colliery (started in 1903) with Gaslitand after nationalization in 1971. Extraction of coal over a prolonged period had resulted in lowering of the ground level which at places was even lower than the bed of the river. It had also caused cracks to develop allover the surface and even in the river bed.

There was an unusually heavy rainfall on the night of 26th September which surpassed all previous records. Against an average rainfall of 1350 mm per year in the Jharia Coalfield, rainfall of 330 mm was recorded on 26th September. The rain had started as a light drizzle at 4 p.m. and soon turned into a heavy downpour from 6 p.m. In just 3 hours between 8 p.m. and 11 p.m., a rainfall of 210 mm was recorded. Strong winds accompanied the rain. At 9.15 p.m. there was complete electrical power failure and the entire area was plunged into darkness in the stormy night. All machinery and equipment operated by electricity, including the main mechanical ventilator, stopped functioning.

The level of water in the Katri River was rising menacingly and must have crossed the danger mark and the withdrawal mark by 10 p.m. but unfortunately on that fateful night no guard was on duty in the second shift to keep a watch on the level of water in the Katri River. While some of the neighbouring mines had withdrawn all persons working below ground by 10 p.m., the management of Gaslitand Colliery remained insensitive to the impending danger and failed to take this basic precaution.

The steam winder of 6 pit had worked upto 10.15 p.m. but thereafter the winding engine driver refused to operate it because there was an accumulation of rain water below the drum which was splashing on to him. He made no effort to bailout the water and neither he nor the banksman took any steps to inform their superiors. Both of them left their places of duty without handing over charge to persons of the next shift.

There were 3 boilers for supplying steam to the winder: two Lancashire boilers and one vertical boiler. One of the Lancashire boilers was under repair. The vertical boiler turned cold in a short time. As the sinder did not operate after 10.15 p.m. steam was not required. It appears that the Lancashire boiler was not stoked and fed with coal after 10.15 p.m. and the adverse weather reduced the steam pressure to much below the operating pressure.

As the main mechanical ventilator had stopped running due to power failure at about 9.15 p.m. apparently all the persons belowground had gathered at the pit bottom of 6 pit by about 11 p.m. and were giving signals to raise them. But their signals remained unattended. These persons did not go to the seconds outlet (No.4 Pit) because they knew that it was not operational. The mine had only four winding engine drivers of whom three were on duty in the three shifts at 6 Pit. The spare driver, as and when available, was used at No.4 Pit. So, in effect, No.6 Pit was only means of access and egress for this section of the mine. On being informed of the dangerous rise in water level of Katri River by the river guard of the third shift, the manager and safety officer rushed to the mine at about 12.30 a.m. The manager instructed the safety officer to stay at 7 Pit and arrange to withdraw the 6 persons employed in that section. He himself proceeded to 6 pit to supervise withdrawal of person there. But he found that the steam pressure was not adequate to operate the winder. He then came to the boiler house. It was about 1 a.m. when he reached the boiler house. Efforts to generate steam on an emergency must have started only thereafter. But it was already too late. At about 1.30 a.m. a sudden gust of cool air forced its way up through 6 Pit. The current of air became stronger and soon it came out with great violence shaking the entire headgear structure. The cage at the pit-top was lifted up and resulted in a violent overwind. The sound of water entering the pit with great force could be heard from the surface. The manager could sense that the mine, was flooded and everything was lost.

It appears that the break in the embankment took place at around 1.15 a.m. and the river entered the old quarry. The water must have been impounded by the retaining wall for sometime but very soon it was washed away and the water entered the old disused quarry which was connected to below ground workings. Water rushed into the underground workings resulting in violent expulsion of air through 6 Pit. The cage at the pit bottom was carried inbye by the force of the water, causing the violent overwind of the cage at the top. The entire mine must have been completely filled up with water in a matter of minutes drowning all the 64 miners who were belowground at that time.

No assistant manager or under manager or overmen had been posted in the, second shift. There was total lack of coordination and absence of discipline culminating in the winding engineman not operating the winder in spite of receiving signals from belowground and the banksman and attendance clerk not taking any action to correct the aberrations. The fireman also stopped maintaining steam pressure in the boiler. Obviously, the mine was being worked in total violation of the safety regulations and standard procedures. This tragic accident has brought into focus the dangerous state of affairs existing in BCCL mines. That 64 valuable lives were lost is not a measure of the magnitude of this disaster. The moot question that needs to be answered is how could such gross violation of safety norms and criminal negligence of duty be allowed to occur in a mine belonging to Coal India, Ltd.